Premier League managers need to be more aggressive

Managers are often too afraid to lose, and it's costing them points in the table

Bournemouth raised plenty of eyebrows earlier this summer when they sacked manager Gary O’Neil. O’Neil had taken over a Bournemouth side that a minus FOURTEEN goal differential after just four matches and ultimately lead them to a 15th place finish and another season in England’s top flight. The job he did was considered so impressive The Athletic gave him a shout in their Manager of the Year considerations.

In reality, Bournemouth were right to sack O’Neil. They finished the season with the third most losses in the league, third most goals conceded, second worst goal difference, and dead last in expected goal difference1. For all intents and purposes that’s a team that should have went down, and if they opted to run back that strategy again this year, it probably wouldn’t end well.

So how did they manage to survive? The short and obvious answer is variance, but as Grace Robertson aptly points out, their survival was down to a different reason. They didn’t draw many games!

Only Leicester City and Southampton lost more matches during the 2022-23 season than Bournemouth’s 21 losses and both will be playing the 2023-24 season in the Championship. Leeds were level with Bournemouth on 21 losses and had better underlying numbers than the Cherries, but they finished with eight fewer points and thus will also be going down. The difference between the two clubs was simple, Bournemouth won four more matches.

This “one weird trick” isn’t just for avoiding relegation. It applies throughout the entire table.

Newcastle only lost five matches last season. That’s the kind of number that should find you in a title race - and sure enough champions Manchester City had the same number of losses while Arsenal had six. But Newcastle only finished fourth, four points behind Manchester United who lost nine times. The difference being Newcastle drew 14 matches. United drew just six and won four more than the Magpies.

When the rules for league football were first created in 1888 the powers that be decided teams would get two points in the table for a win and one for a draw. Nearly 100 years later the men in charge of the English Football League wanted to encourage more attacking football and decided to award three points for a win, though it would take another 13 years for the rest of the world to follow suit.

Here’s the problem. They didn’t go far enough!

We’re still awarding too much for a draw. We praise teams for being “unbeaten” when in reality not winning is bad, regardless of whether you lose or draw.

In 2016-17 Jose Mourinho was praised for going unbeaten for 25 consecutive Premier League matches during his first season with Manchester United. The media and Mourinho played that stat up but that unbeaten run didn’t do much for United. When it started United were seventh in the table. When it ended they were fifth, still sitting outside the Champions League places.

While United went 25 games unbeaten, they were hardly dominant. They dropped points in almost as many matches (12) as they won (13). Say during that 25 match run instead of drawing 12 times United only drew five times, and with those other seven games they lost three of them and won the remaining four. That would have given them five more points over that 25 game span, which would have put them in third place.

Third place with three losses seems better than 25 games unbeaten while you’re still on the outside looking in at the Champions League2. But Mourinho can brag about going 25 straight unbeaten.

Look at the table for the 2022-23 Premier League season. Now instead of sorting it by points, sort it by wins. It looks almost exactly the same as the final table with one exception, if things were based only on wins Everton would have finished one spot lower than Leicester City. Wins are pretty indicative of the quality of a team.

A win is now worth three times as much as a draw, but managers haven’t seemed to catch onto that. Rather than understanding how much more they have to gain by winning, their in game decisions still generally look as if they’re more afraid of losing.

A few weeks ago I published the substitution data I collected from the 2022-23 season. Again I’ll mention the sample does not include all 20 teams but the traditional “top six” clubs, Brighton, Newcastle, Everton, and Leicester City so the data is going to skew more towards the good teams, but there’s still plenty of good stuff to look at here.

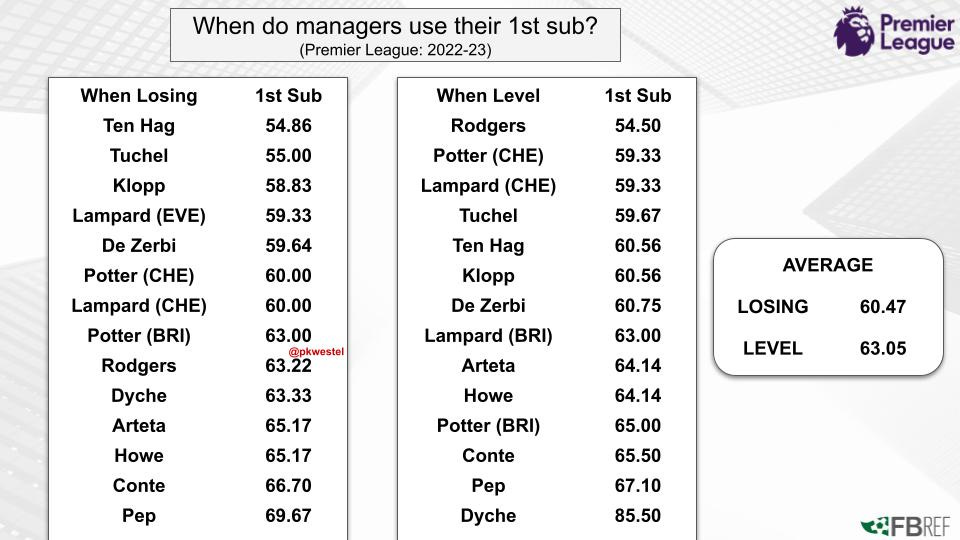

The first thing to look at is when managers make their first change when they’re not in a winning game state3.

On the whole managers wait three more minutes to make changes when scores are level then they do when they’re behind. The logic seems sound, when you’re trailing you have nothing to lose, if you concede another goal it doesn’t really matter so you can risk more to score. When things are level you’re still working with a point, if you concede now you have nothing. There’s more to lose so you give your starting XI a bit more time to figure things out, even though in reality there’s actually a lot more to gain.

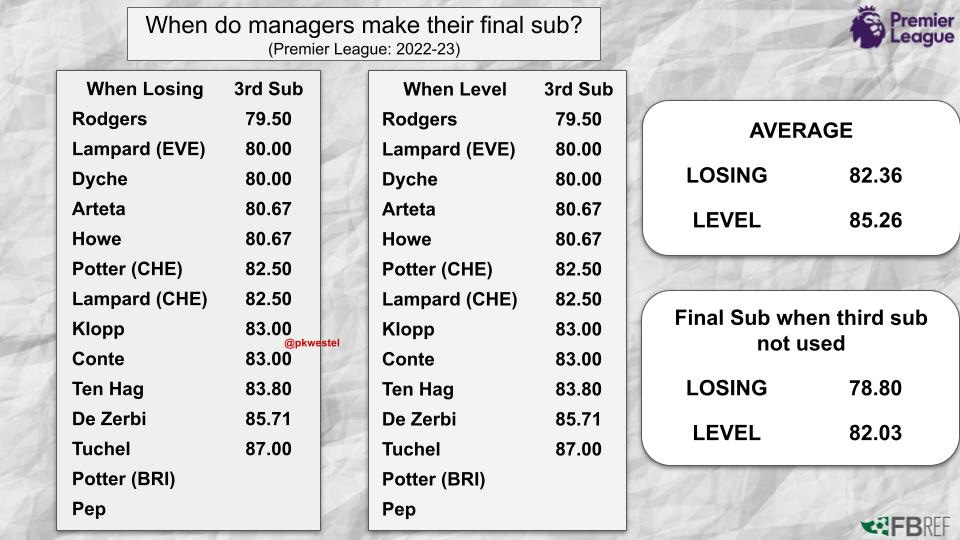

It’s not just about when you make your first change though. Sometimes the game state changes after your first substitution and things become level later on. Sometimes your first two subs don’t work, and managers have to roll the dice even more. But are they? Let’s compare when managers make their last sub when they’re trailing vs when things are level.

Again they’re waiting an additional three minutes when things are level compared to when they’re behind. That final sub is coming with about five minutes left to play plus stoppage time.

That’s if they’re making their final sub at all. In the sample of 380 unique matches, 85 of them ended in a draw. In 44 of the 85 matches (51.76%) that ended in a draw managers still had available substitutions left in their pockets - the highest amount of all three results. As you can see, the average time of the second sub when the third isn’t used is also just over three minutes later when scores are level.

Bringing on a player with 5-8 minutes to go plus stoppage time just isn’t enough time to impact a match, and often times, that’s the whole point. When scores are level it’s amazing how many times managers use their final substitution to remove an attacking player and bring on a more defensive player.

Managers would rather protect the point they have then fight for an extra two. Perhaps it’s easier to face the media and the fans with a point in your pocket rather than nothing, but this is ass backwards thinking. When things are level, the reward of gaining an extra two points in the table with just one goal far outweighs the risk of losing one point by conceding a goal. Managers who consistently take this risk are probably going to be rewarded over the course of the season.

In the aforementioned sample, 99 times did managers make their first sub when the game state was level. 47 times the game ended with a result other than a draw. 27 times it ended with a win and 20 times it ended with a draw. Just over one fourth of the time managers made their first change with the scores level they went on to win, while one out of every five times they ended up losing.

It may not seem like much but that’s a pretty decent swing. Put it another way. If all 99 matches had ended in a draw you’d come away with 99 points. Instead you lose 20 points for the matches lost, but you gain an extra 54 points for the 27 matches won. Ultimately you come out 34 points ahead.

Like I mentioned before, the sample is primarily teams at the top of the table but let’s isolate Leicester and Everton who were both in the relegation battle.

17 times those teams made their first non-injury substitution when scores were level. Twice they went on to win, six times they lost, and nine times result held. That comes out to 15 points from the 17 games. Despite these teams being really bad, they only lost two points. Had they won more game, they would have broke even.

Let’s isolate it even further. In Brendan Rodgers’ 31 games in charge of Leicester he was the most aggressive manager in terms of making changes, having the earliest average first change when level, and the earliest third change when either level or behind. In fact, Rodgers’ first sub when things were level was nearly nine minutes earlier than when he was behind.

Between Rodgers and Dean Smith, Leicester were level when making their first change nine times this season. Three times the result held, four times they went on to lose, and twice they won. That’s a break even score. Had they won just one more match, they’d have finished level with Everton and beaten them on goal difference. They’d have needed to not lose twice in order to achieve the same result with draws.

Even at the bottom of the table it’s worthwhile to go for the win, but now that we’ve stripped out our relegation battlers let’s look again at the top of the table.

For the clubs that finished in the top eight of the table this year (less Aston Villa), 82 times their first sub was made with scores level. The result held in 43 matches while they ended up winning 25 times and losing just 144! Nearly one out of every three matches were won while only one out of six were lost. In 10 games that’s roughly three wins and one and a half losses, an additional 4.5 points.

How big is that? Well 10 times this season Manchester City made their first change when scores were level. They won four of those games and lost three, for an additional five points - the margin between them and runners up Arsenal. Arsenal were level when they made their first change seven times, they won two and lost one.

Newcastle were level 15 times when they made their first change this year. They won only two of those matches and lost one, but when things were level Eddie Howe’s second (83.00) and third (87.00) changes came exceptionally late. He was protecting a point rather than going for the win. That’s the difference between third and fourth place.

If you have Champions League ambitions, not only should you be more aggressive in going for wins, you need to be. Managers need to remember that in most of the games they play, they’re the better team, and thus bringing on fresh legs and giving them enough time to make an impact is going to benefit you more often than not.

Yes every so often being aggressive with your changes is going to cost you a match and you’re going to have to face the media after a loss. But if you stay consistent over the course of the season you’ll end up winning more games, moving up the table, and having more of those fun enjoyable press conferences.

We shouldn’t be praising managers for not getting beat. The name of the game is to win the most points and finish as high as you can in the table. Draws don’t help you move up the table, wins do. The managers that aren’t afraid to lose understand they may actually lose one or two more games, but the wins they gain will help them much more than the losses hurt.

Yes some of that has to do with those big losses to Manchester City, Arsenal, and Liverpool during the four game Scott Parker era, but over the last 34 games of the season they were 17th in xPTS per Understat - just 0.68 points out of the relegation zone

United would qualify for the Champions League by winning the Europa League - but the Champions League group stage payouts aren’t as high for the Europa League winner as they are for the top four finishers. Financially, this would hurt United long term

It should be noted that these averages don’t include when managers used the halftime window as an “extra” window (IE they made a change at halftime, then used three more substitution windows - this happened eight times when scores were level in the sample). If a manager made a halftime change but only used one or two windows in the second half, it’s reflected in the averages

Five of those wins belong to Chelsea, which is impressive because they only won 11 games all season. Even when you’re bad you’re still likely to gain points.