So your stats are great, but what comes next?

Stats are great for analyzing players but it's often more important to look beyond the accumulated statistics and ask, what does the player do with the ball after the statistic?

I’m always amused when people say they don’t like stats in football. At their core, stats are just counting specific things, which has always been a part of football.

Goals obviously reign supreme, so it didn’t take long for folks to realize we could figure out who the most valuable players are by counting how many goals everyone was scoring. Eventually we realized there was some value in that winger who kept getting the ball to the striker so he could score all those goals so we started counting assists too.1 Shortly after that someone said “you know players that take more shots than others tend to score more goals because they have more opportunities to score so maybe we should start counting those too.”

It was only when we started trying to measure the quality of those shots that things started getting a little advanced. Getting all those shots is nice, but we wanted to know how many goals you can expect someone to score from those shots. Thus expected goals was born, and the disdain for stats really took off - even though “ah he should have finished that” has long been a phrase in the lexicon of football fans.

Nevertheless I still don’t understand that absolute disdain for stats. This isn’t like baseball where advanced stats were born out of complex calculations. For the most part, this is simply counting.

Roy Keane’s job wasn’t to score or assist goals so why should those be the only metrics available to judge him on? If his job was to make tackles, win duels, and win the ball back wouldn’t it make sense to count how many times he did those things in a given match? If Michael Carrick’s job was to effectively pass the ball from the back to the front, shouldn’t we count how often he did it so we can measure how effective he was?

While stats were becoming more prevalent over the last decade they were still mostly a niche subject. That changed in April 2020 when Fbref launched their partnership with Statsbomb. The plethora of data that was now publicly available helped stats become more mainstream. Though there are still plenty of people using stats terribly,2 this was undoubtedly a good thing.

The one thing all stats people will tell you is even though the numbers are proving to be right more often than not, you still need to actually watch football. It’s only by watching matches that we can see what the numbers actually mean, as well as either what the numbers aren’t telling us or what the numbers are missing. The thing about stats is, they’re always evolving.

That leads us to the obvious question. What comes next?

Like the entire concept of stats in football, that question is twofold. You can look at it from the stats perspective of, everything we have is great but incomplete, what new metrics are we coming up with to help us understand the game even further?

Or you can look at it from a more football perspective, where you take the stats and ask, what does that actually mean? In other words, sure that particular stat is nice, but what are you doing with the ball after accumulating that stat? That’s what really matters.

The Aaron Wan-Bissaka Declan Rice Corollary

3A few months ago Mark Thompson wrote a superb article looking back on Manchester United’s £50m signing of Aaron Wan-Bissaka. The gist of Thompson’s article was, “what did we miss?”

In three years Wan-Bissaka has not developed into the player United hoped he would. As these things always work, you’ll hardly find a person these days who didn’t immediately know Wan-Bissaka would always be a bust and United should have signed someone else4.

It’s easy to sit here in 2022 and talk about how much United whiffed on this one. Names like Reece James and Tariq Lamptley are routinely mentioned by fans as players United could have gone for, even though in the summer of 2019 neither had ever played a first team match5 and both being Chelsea property there was no chance either would be sold to Old Trafford. But the main point is - and as Thompson does in his article - you can’t look at this from a 2022 perspective. Manchester United weren’t making that deal with 2022 knowledge, they were making it with 2019 knowledge.

2019 isn’t that long ago and yet football has evolved significantly since then. That is especially true when it comes to data analytics. For the public, this was still the pre Statsbomb-Fbref days, and while there was data out there, we simply didn’t know as much then as we do now. Even clubs, who are more advanced than the public (I mean, you would really really hope that’s true) were still learning.

If you’re going to look back at that deal you have to do it through a 2019 lense. At the time of the deal, the two biggest right back prospects in England were Trent Alexander-Arnold and Aaron Wan-Bissaka. The two were seen as almost polar opposites. Alexander-Arnold was mesmerizing attacking talent but struggled defensively. Wan-Bissaka was a lockdown defender who just needed to develop the attacking parts of his game. In the spring of 2019 it was not uncommon to hear pundits arguing about whether Wan-Bissaka or Alexander-Arnold was the long term right back of England’s future.

It’s important to remember that Wan-Bissaka was very highly rated, as Michael Cox even noted in The Athletic recently.

Take Wan-Bissaka and compare him with Andy Robertson. It might seem ludicrous to say it now, but upon their respective moves to the north-west, Wan-Bissaka was a better player. A different player, certainly — renowned for his defensive solidity more than his attacking drive, and it’s generally easier to coach an explosive attacker into a reliable defender, rather than vice-versa. And yes, price tags don’t entirely reflect a player’s quality, but there’s a reason why one cost £7 million and the other cost £50 million. One was simply rated more highly than the other.

Since then, their trajectories have differed enormously. Robertson is now the best left-back in the country and arguably the best in Europe, while Wan-Bissaka is struggling to get into the Manchester United side, and is the go-to example of a footballer who won’t suit the new regime, which is likely to be based around technical, attack-minded football. That’s because of Wan-Bissaka’s own shortcomings, but that’s not entirely his fault.

It would be fascinating to see what would have happened if Wan-Bissaka had been playing under Klopp for three years, and Robertson under Solskjaer and Rangnick. Would their situations be entirely reversed? Perhaps not quite. But there’s a very good chance Wan-Bissaka would be regarded as the better player — considering he was rated higher to begin with, and would have been playing under a better manager.

The stats loved Wan-Bissaka. He was a shutdown defender that could lock down an entire flank on his own allowing United to focus the rest of their resources elsewhere. The questions were always going to be about Wan-Bissaka’s attacking ability. Seeing as he was playing for Crystal Palace, a team that primarily played in a low block, he didn’t have great numbers but as Statsbomb explains, there was reason for promise.

That’s the issue that surrounds Wan-Bissaka. Very few are questioning whether his defensive capabilities will translate at a bigger club, because he’s shown enough this season to suggest that’s a rather safe bet. Rather, will he be able to exist as a functional cog in the wheel offensively? Furthermore, just how good is Wan-Bissaka currently offensively? Is there enough upside that he could grow into a net positive as a play-driver? These are some of the questions to ask when evaluating Wan-Bissaka as a talent, and whether it’s a smart idea for United to allocate major resources (not just the transfer fee but wages as well) towards him. Certainly, that mystery on Wan-Bissaka’s offensive ceiling is in part due to playing on a decent but unspectacular attacking side in Crystal Palace last season. They ranked 12th in expected goals from open play and 8th in shots. If he had played on a more expansive attack, perhaps we would’ve had more of an idea on his upside as a play-driver.

If one was to concoct an argument in favor of Wan-Bissaka’s offensive ceiling, a major component would be his dribbling abilities and the luxuries it affords him that not a lot of fullbacks possess. As part of the responsibilities that modern day fullbacks have, being able to beat their marker off the dribble in the middle and final third has become much more of a necessity. Wan-Bissaka certainly has that in his skill-set, his 2.01 dribbles per 90 is nearly three times the league average rate for fullbacks in the Premier League, and his dribbling map below shows a very healthy amount of dribbles into more advanced areas along with the actions that followed.

So the question is, what did we miss?

Wan-Bissaka was very good at beating his man and had mediocre crossing ability. His lack of numbers would improve in a team that attacked more. To some degree, they did6. So what did we miss?

That’s the question that Thompson explores in his article which leads him to raising the point of “what did you do next?”

Beating a man on the dribble is great, but unless you’re doing it in the final third and then launching a cross, you need to do something with the ball after completing the dribble. Typically that means passing to a teammate.

Wan-Bissaka is not only not a dynamic passer, but he’s hardly even a good passer. That quickly becomes a problem. In the final third, if you can only whip in mediocre crosses and can’t pick out a pass you become one dimensional really quickly. Outside the final third though, you become useless at best and a liability at worst7.

Beating a man 1v1 in buildup is great. It eliminates a player from the defense, causing everyone else to scramble around and cover. This leads to defenders being out of position and opportunities for the attacking team. But in order to take advantage of that you have to be able to make the dynamic pass.

If you beat your man on a dribble but then just have to hold things up, the stat doesn’t really help you.

Wan-Bissaka would often beat his man, but his lack of passing ability would lead to him opting for a safe square pass, giving his man time to get back into position and negating any advantage United gained from his successful dribble.

This is where we are with Declan Rice.

The West Ham midfielder is the latest hotshot midfield prospect and the subject of endless rumors of a £100m move every summer. The knock on Rice coming into this season was his ability to progress the ball in the middle of the park8. Rice has seemingly addressed that this season. His progressive passes rose from 2.94 per 90 to 4.33 but his progressive carries jumped from 5.16 to 7.43. That’s a pretty impressive increase.

But just taking those numbers at face value would be doing yourself a big disservice. By now you should be asking, what is he doing after making the progressive carry?

The answer is, not much.

While Rice’s progression numbers have increased nicely - to around the number you’d like to see from a European quality double pivot player - nothing else really has. His key passes have hardly increased. His xA per 90 has stayed exactly the same - so he’s not creating any more chances directly. Indirectly his shot-creating actions per 90 are up less than a third of a shot per 90, hardly anything of consequence especially when factored against the large increase in progression and getting the ball into the final third.

Rice is a central midfielder playing in a double pivot. This season he’s had more freedom to make driving runs forward, which makes him an important component to West Ham’s attack. It’s his job to get the ball to the dangerous players in positions where they can be dangerous. Part of what he should be judged on isn’t just doing those individual things but how those things are helping West Ham overall.

For all the increase in progression and moving the ball into the final third, it’s not making West Ham any more threatening. Last season the Hammers were taking 12.16 shots per 90 with a non-penalty xG of 1.33. This season those numbers have dropped to 12.0 and 1.2 respectively. They’ve gone from scoring 1.53 non-penalty goals per 90 to 1.37.

Those drops may seem minuscule but when you’re getting over three and a half more progressive actions and over four more final third entries from your central midfielder alone, you’d expect those numbers to go up. Yet the bulk of West Ham’s creativity is still coming from the outside. Rice is driving the ball forward, but once he gets there, he’s not playing the incisive passes through the defense. Rather he’s stopping, holding things up, playing the ball out wide, doing things that take time and allow the defense to get back into position and nearly render the previous work moot9.

You may want to attribute some of this to West Ham not having a direct passer or central playmaker in their team. After all, Rice is just the midfielder. He’s done his job by getting the ball forward. But we don’t have to look far to see that even if you do have that central playmaker and dynamic passer in your team, if your midfielder isn’t doing this you will still struggle.

Per Fbref, the most similar ranked player to Declan Rice in Europe is none other than Scott McTominay10.

This season McTominay has also seen a tremendous improvement in his progressive actions per game. That improvement was dialed up even more when Ralf Rangnick first arrived at Old Trafford.

In Rangnick’s first five games in charge McTominay was getting nine more touches per 90 than under Ole Gunnar Solskjaer. His passing became a lot more direct, and his progressive actions (passes and carries) rose by five and a half actions per game.

But how did that affect Manchester United? They saw an increase in possession (53.22% to 58.00%) but turned that into nearly a whole shot fewer per 90. Their non-penalty xG was as close to stagnant as it can be (going from 1.36 to 1.37). Their goals per game dropped from 1.51 to 1.2.

For as good McTominay was individually, he wasn’t making the team any better. Turns out when you have a midfielder who dawdles on the ball and then plays it out wide giving time for the defense to reset…

…can have a negative impact on your attack. It’s been common this season for opposing teams to let McTominay have space and challenge him to take the game to them. He usually doesn’t.

Progressive passes aren’t the same as line breaking passes. Line breaking passes tend to be incisive, getting the ball to players in a place where they can quickly make a situation dangerous. Progressive passes are great, but they don’t always tell the whole story. You can rack up the stat while still being a bad passer quickly rendering it useless. Take the example below where McTominay makes the progressive outlet pass, but because it’s a bad pass it eliminates United’s chance at a break and puts his teammate in a poor situation where he’s bound to lose the ball.

There’s very few things in modern football more important than your ability to pass. Every position needs to be able to do it including fullbacks, centerbacks, and as Liverpool and Manchester City show us, even your goalkeeper11.

That’s what we missed with Aaron Wan-Bissaka. That’s what far too many people seem to be overlooking in Declan Rice. Both players have plenty of positive attributes but if you don’t have the passing ability to follow the things you can do, it’s a real disadvantage. What comes next?

Answering that question is the latest challenge for the stats people. How do we take the actions we’re seeing on the pitch and measure what kind of impact they have on the team overall.

People are - very much - working on this, which is good, but quickly takes us to the next problem of publicly available. Understat currently has xG Chain and xG Buildup metrics available, but those are also somewhat flawed metrics and understats model is… you know.

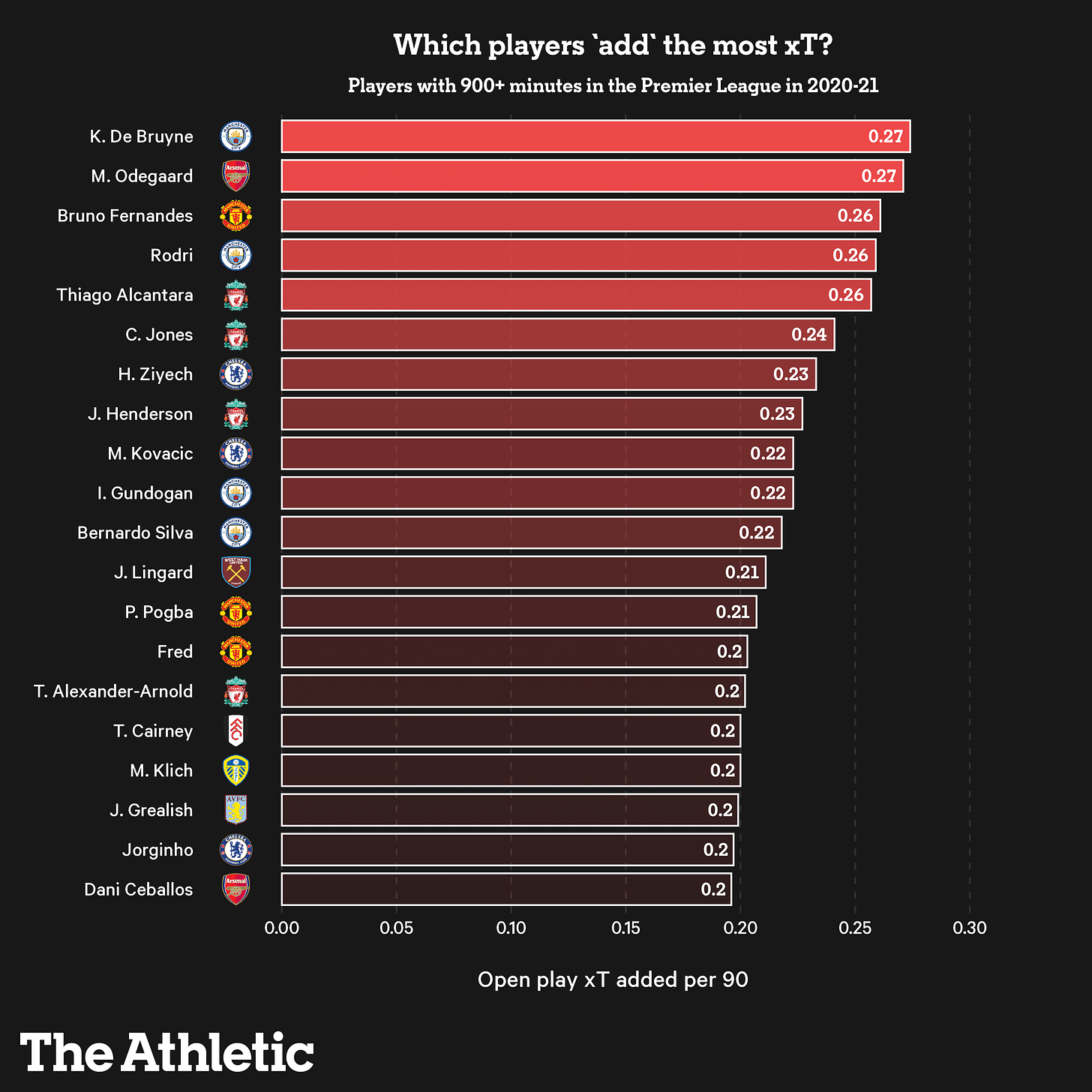

At the end of last season The Athletic wrote a great introductory piece on the newest metric we have, expected threat.12 xT is the newest way of measuring the value of every pass that’s made on the pitch, which is great, but the real gem of this Athletic piece was where they looked at who had the highest xT from the actions that came immediately after their pass. In other words, who’s getting the ball to players in areas where they can be dangerous?

This is something very valuable. Unfortunately, expected threat is one of the more complicated “advanced” metrics and there’s not too much publicly available xT data out there13.

Hopefully this is something that gets advanced in the future. Otherwise the more stats become mainstream the more you’ll see stats being used badly14. The more ways we can easily measure players and their impact the better.

What comes next?

A question for everyone to ponder.

“Eventually” is doing a a lot of heavy lifting in that sentence. It wasn’t until the mid oughts that assists started to really get recognized. Thierry Henry’s “record” of 20 assists in a single season was essentially awarded retroactively. It only started commonly getting acknowledged during the 2015-16 season when Mesut Ozil threatened to break it. Even now the Premier League, Fbref, and transfermarkt all have different totals for how many assists Paul Scholes had.

Funny how many people who for years were anti stats now commonly cherry pick numbers without context or without adjusting for possession to try and further their agendas

I’ll be perfectly honest, I have no idea if I’m using the word corollary correctly here

You know, despite the signing being wildly celebrated at the time the way all United signings are

James played on loan in the Championship, so a first team Premier League match but I just felt that was wordy

Overall Wan-Bissaka’s attacking output from his final season at Crystal Palace to his first at Old Trafford didn’t jump too much but the splits from the first half of the season to the second showed a stark improvement. His four assists were the joint most United got in a season from a right back since 2003 (Rafael da Silva also had four in 2012) so there was reason for optimism.

Wan-Bissaka would eventually become a liability

Something he very much did not show during the Euros last summer and it really held him and England back

Rice remains a very good player, but if any top team thinks that paying premium money and adding him will significantly boost their midfield, they’re going to be severely disappointed.

Poor man’s Declan Rice

And as David de Gea shows us, if your goalkeeper can’t pass, it’s a massive liability

Please do not mistake this for me saying they created it

There are some people who have xT data and make it available on GitHub but this data is even harder to obtain if you don’t know how to code.

And we haven’t even touched WhoScored or FotMob ratings…

Funny reading this in 2025, after the past two seasons Rice has had after premium money was spent on him.

Excellent article. It's really a new field to explore and make stats much more closer to the truth.